by Anna Campbell

From Health First, June, 1991

Approximately 4,000 children with Down syndrome are born each year in this country, accounting for about 1 per 1,000 live births. A Down syndrome child may be born to parents of any age, but the incidence is higher for children born to parents over 35.

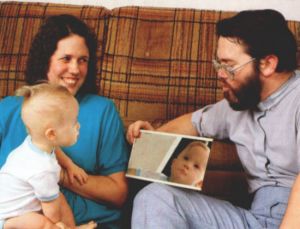

Last January, David Rubke, Lutheran minister and administrator for Catawba Valley Lutheran High School, and his wife, Becky, had their fourth child, Timothy. He was diagnosed at birth as having Down syndrome. Becky was 38.

"I knew because of my age that there was an increased chance of having a Down syndrome baby," she says, "But I wouldn't have had an abortion anyway, so there was no need for me to undergo an amniocentesis. It would have only made me anxious during the pregnancy."

Timothy is now 14 months old, but looks younger. At first glance, it is hard to distinguish him from a normal baby. Upon closer inspection, one notices the almond shape of his eyes, and the poor muscle tone characterized by a noticeable "floppiness" of his body. But what is most apparent is his cheerful disposition and his ready smile.

Down syndrome is an abnormality characterized by an extra chromosome. Most people have 46 chromosomes in each cell, 23 pairs consisting of one chromosome from the father's sperm and one from the mother's egg. A person with Down syndrome has 47 in each cell. The extra chromosome can come from either the father or the mother.

The extra chromosome is usually located in the pair designated number 21, and for this reason, the scientific name for the abnormality is trisomy 21. Approximately 95 percent of children with Down syndrome have this form of chromosomal abnormality (Two less common types of Down syndrome are known as translocation and mosaicism).

Most people are familiar with the physical features associated with Down syndrome, but many are confused about the extent of mental retardation that can be expected. In fact, there is a wide variation in the degree of mental retardation among people with Down syndrome. It cn range from minimal to severe, with most falling within the mild to moderate category.

It is impossible to determine at birth exactly how impaired the child's development will be.

"The Developmental Evaluation Center does the first evaluation at about a year old, and another at two years to see how far the chld has progressed," explains Becky. "Timothy is 'mildly delayed' at this point. From there the categories go to moderately to severely to profoundly delayed."

It remains to be seen how far Timothy will eventually go. David and Becky, of course, have high hopes for their child's future.

"We hope that he will be able to hold down a job and be somewhat independent in his adulthood," says Becky. "Look at Chris Burke, for instance (who plays Corky Thatcher, a teenager with Down syndrome on the TV show Life Goes On). He holds a job as an actor and travels around the country speaking on behalf of people with Down syndrome. He is living proof of what they can accomplish."

The future is a long way off. In the meantime, the Rubkes are focusing on what Timothy can learn now. The time and effort it takes to teach him is considerable, but they know they must persevere if he is to reach his full potential.

Down syndrome experts are emphatic about the point that these special children can usually do most things that any young child can do (walking, talking, dressing themselves and being toilet trained). The difference is that Down syndrome children learn these skills a little later than others.

"When we're working on new things with Timothy, we work ahead of where a normal child his age should be," explains Becky. "Hopefully, that way, by the time he reaches that age he'll be as close as possible to the normal level."

The earlier a child with Down syndrome is given individual, specialized attention, the better chance he has of excelling in life. This is where Early Childhood Intervention Services (ECIS) comes in. A division of Catawba County Mental Health, ECIS servies families with developmentally disabled children up to three years old.

ECIS personnel have worked with Timothy from birth.

"He has a speech therapist," explains David. "When he was born he did not even know how to suck. He has low muscle tone in his mouth. If a child does not know how to suck, he will have major speech problems. It makes sense, even though most people have never thought about it.

"It wasn't that he had an inability to suck. It was something he had to learn. The suction pads in his mouth are small, making it a slow and inefficient process. They taught us how to stroke his mouth to stimulate nerve endings. We used a special brush and toys with lots of texture. Eventually, he caught on. You can take nothing for granted with these children," David says.

"Of course, I wanted to breastfeed him," adds Becky. "It was difficult for me to give that up. But I finally realized that if he was going to be happy and I was going to be happy, we'd better go to the bottle."

Timothy, his family and his ECIS therapist, Sharon Barlow, are constantly working on building up his muscle tone so that he can learn to sit and eventually walk.

"Sitting takes place later on," Becky explains. "He does sit in a high chair. It has enough back support so that he doesn't fall over. He will probably be two or older before he learns to walk. In the past month he has learned to bear weight on his feet."

The therapy does not take place only during set periods of time. Rather, it is a constant process.

"I spend five minutes here and five minutes there on his therapy," says Becky. "I'll rub his feet or play pat-a-cake, to teach him to put his hands together in front of him. Teaching him takes a lot of patience. He loses his patience more than I do. But when he learns how to do something new, it's really exciting."

The Rubkes have a tremendous appreciation for the support of ECIS personnel, not only for their professional help and advice, but for the genuine compassion they display.

"To the people at Early Intervention, it's not just a job," says Becky. "They become really attached to the children. These kids are their kids, too, and the kids love them for it. I want to know that my child is getting help from someone who knows him and cares for him as a person."

An equally important aspect of Timothy's therapy is learning to talk.

"He has formulated a few words," Becky relates. "He calls everybody 'Da Da.' He can say 'goodbye' and 'thank you.' But he doesn't know what he's saying yet. To him, they're just sounds."

There are three other children in the Rubke family besides Timothy: Rachel, 14, Jonathan, 11, and Michael, 8. They face special problems of their own, such as learning to cope with less attention from their parents, and dealing with the fact that their brother is "different."

ECIS offers a program for brothers and sisters of Down syndrome kids called "Sibs Too." It is a workshop designed to help siblings work through their problems. The course helps them understand what it's like to be handicapped by incorporating such devices as blindfolds, canes and wheelchairs. Becky describes the program as very beneficial.

"Really, there are no problems with the other kids in our family," Becky remarks. "They are very accepting of Timothy. Of course, we've talked a lot about Down syndrome with them. I think it will be a little harder for the children later on (when it becomes more evident that Timothy is behind in his development). It might be hard for them to understand why they're being treated funny because their brother has a problem."

At the moment, Timothy is obviously the mascot of the family. Fourteen-year-old Rachel has practically adopted him as her own child.

"Because of Timothy, Rachel now wants to work with developmentally delayed children when she gets out of college," Becky says.

Having a large family is probably to Timothy's advantage.

"With three brothers and sisters, Timothy has a tremendous amount of social interaction," Becky states. "That's very important in his development. The more stimulation he gets, the quicker he's going to advance. He's used to being around a lot of people anyway. We don't hide him away somewhere."

Society's acceptance of Down syndrome children is an issue that the Rubkes have recognized. But they feel that acceptance is becoming more prevalent.

"Down syndrome babies are cute and cuddly," Becky points out. "Most people are quite accepting at this stage. But that tends to change later on, when they're not quite so cute anymore."

"We watch Life Goes On regularly," David adds. "That show has increased public awareness of Down syndrome. It brings prejudice and other issues out into the open, and shows how much people with Down syndrome can achieve today."

One problem the Rubkes have had to struggle with is the natural tendency to compare Timothy to other children his age.

"At seven months, other babies are sitting up," David observes. "Timothy is fourteen months old and still can't. I'm starting to see this. This is becoming real."

Becky agrees.

"You do begin to look around and see some of these differences. With a normal child, you don't pay as much attention to these things. You say, 'Well, kids all develop at different rates,' and leave it at that."

She recalls an Intensive Care Nursery reunion her family attended at Catawba Memorial Hospital. "The room was full of parents and toddlers, and intensive care nurses, who were very helpful when Timothy was born. We enjoyed it a lot. The hard part was looking at other babies Timothy's age or younger running around. It felt strange."

The experience of caring for Timothy has had a profound impact on the Rubkes' lives.

"It has made me a much better pastor and teacher," David declares. "Before I had kids of my own, I was extremely critical of other parents. Any difficulties we have had with any of our children have made us much more compassionate and ready to listen. It's hard raising kids. Any kids."

Timothy has also had an impact on Becky's career. She has made the decision to stay home and be full-time mom to her kids.

"I was church secretary for three years," she says. "I went back after Timothy was born, and kept him in the nursery while I worked. But it was hard. Just feeding him was a major task. The people I worked with were willing to help, but it was taking too much time. They wanted Timothy to come first, and the job to come second. It really wasn't fair to them."

"I came to the realization that I needed more time to devote to my kids, all my kids. I'm not supermom. I am still the organist at my church, and that takes a lot of time itself.

David and Becky are quite aware of the problems the future may hold.

"What will happen when he gets to be 23 or 24?" David asks. "By that age, most kids move and get their own place. Timothy may be here forever. If I die, how is he going to be taken care of? I'm starting to look harder at the future. We have to start thinking of these things already."

But in the meantime, the rewards of raising this special little boy cannot be denied. His sunny smile and warm hugs speak a universal language--the unquestioning, unconditional love of a child. Looking into his bright blue eyes, it is apparent that he knows a happiness few of us can understand.

"Certainly Down syndrome children are more pleasant than others," Becky says. "Most of them are a lot happier. The world's problems don't trouble them as much as they do other children."

Timothy's happiness has a tendency to rub off on his family. Every time he smiles, laughs, says a new word, or accomplishes something new, his parents, brothers and sisters rediscover the joy of life right along with him. They serve as Tiimothy's teachers, yes, but he has a lot to teach them as well. And that, perhaps, is his mission--and the mission of all those with Down syndrome.